The Endangered Species Act (ESA) is the most comprehensive law protecting imperiled plants and animals in the world.

Because of the ESA, hundreds of plants and animals have been saved, including some of our most iconic birds: the American Bald Eagle, the California Condor, the Peregrine Falcon, and the Whooping Crane.

The California Condor, for example, the largest land bird in North America, became extinct in the wild in 1987 when the 27 surviving birds were captured. Captive breeding began in 1991. Thanks to the provisions in the ESA, an estimated 558 Condors now live in the wild.

A California Condor soars in the wild because of the provisions in the ESA. Photo credit Georgi Baird, Shutterstock

How the Endangered Species Act Works

Any person or organization can present a petition to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) or to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to list a species that they believe is at risk of extinction. If the species passes the gantlet of scientific due process and is listed as threatened or endangered, the federal agency listing the species will develop a plan for protection and recovery.

Once a species is listed, it’s unlawful to “harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage” a member of the species without a “take” permit from the listing federal agency. It’s also against the law to destroy critical habitats of listed species.

These restrictions were used to good effect in the recent six-year fight to defeat the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Dominion Energy had to reroute its planned 600-mile, fracked-gas pipeline around Shenandoah Mountain because the endemic and imperiled Cow Knob Salamander lives there.

The Endangered Species Act Has Limitations

The ESA is a good law, but pernicious politics, inadequate funding, and limited time plague its efficacy.

Listing a species takes a lot of time, and the imperiled species may be too far gone before federal protections are in place. For example, Green Ash, White Ash, and Black Ash trees are dying at an alarming rate. Although they are considered “critically endangered” by the International Union of Concerned Scientists, they aren’t even candidates for listing with the USFWS.

Funding for federal protection and recovery is at the discretion of Congress and the agency listing the species. It’s often the case that unglamorous species don’t get adequate funding for their recovery plans.

Tennessee’s Snail Darter–Classic Example of Political Interference

Perhaps the greatest limitation of the ESA is pernicious politics. A classic example of how politics can undermine species protection is the construction of the Tellico Dam on the last free-flowing tributary of the Little Tennessee River. In 1975, the discovery of a newly listed endangered species of fish, the Snail Darter, in the Little Tennessee tributary stopped the construction of a hydroelectric power dam by the largest utility in the country, the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The utility lobby convinced Congress to create a separate committee to review the federal listing process. Much to the chagrin of the utility lobby, the committee, referred to as the God Committee, ruled in favor of the fish. The utility lobby eventually prevailed when Congress passed a rider on a military funding bill that exempted the Tellico Dam from the ESA. Construction of the dam was completed in 1979. The endangered fish was transplanted to other river systems in southeastern Tennessee. It was delisted by the USFWS in 2022 due to recovery.

Almost 50 Years Later, It Happened Again

The Roanoke Logperch is a federally listed endangered species. Its discovery in the path of the embattled Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) stopped construction. The U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed approvals for the USFWS Biological Opinion and Take Permits for the third time on July 11, 2023. MVP and West Virginia’s Senator Joe Manchin successfully got Congress to exempt the Mountain Valley Pipeline from federal permits. Environmentalists sued on the grounds that the exemption was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court overruled the dismissals, and MVP construction is underway.

The Roanoke Logperch is an endangered species in the path of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Photo credit Noel Burkhead, USGS, Wikipedia public domain

Ash Trees and Shrikes

In a span of just five years, I have witnessed the death of almost every Green Ash tree in Augusta County, Virginia. In the last 20 years, Loggerhead Shrikes have disappeared from the hedgerows on our farm. Only a few pairs remain in Virginia.

The ash trees are dying because of the Emerald Ash Borer, an invasive insect from China. We don’t know why the shrikes have disappeared.

Scientists, volunteers, and government agencies are working hard to keep ash trees and shrikes from extinction. Injecting the trees with insecticide kills the insect in its borer stages. Three parasitic wasps that kill the eggs or larval stages of the borer have been approved for release.

Dr. Amy Johnson, Director of Virginia Working Landscapes holds a banded Loggerhead Shrike. Photo credit Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries

The Loggerhead Shrike is listed in Virginia as “critically imperiled” for breeding and is a listed “threatened” species. The Smithsonian Institution breeds these shrikes in captivity at its Front Royal, Virginia facility. It releases young ones in Canada and tracks them as they migrate south. One was spotted in Swoope in 2016.

Sadly, the USFWS removed 21 species from the Endangered Species list this year because they had become extinct. They are gone forever.

Why Save an Endangered Species?

Some may say, so what? Life goes on. It’s the march of evolution. Indeed, the world just keeps turning.

But the loss of a species is the loss of a piece of life’s giant puzzle, a key that could open a door of opportunity, the source of a substance that could cure cancer.

“The last word in ignorance is the man who says of a plant or animal: ‘What good is it?’” wrote Aldo Leopold, the father of wildlife conservation in America, in the mid-20th century.

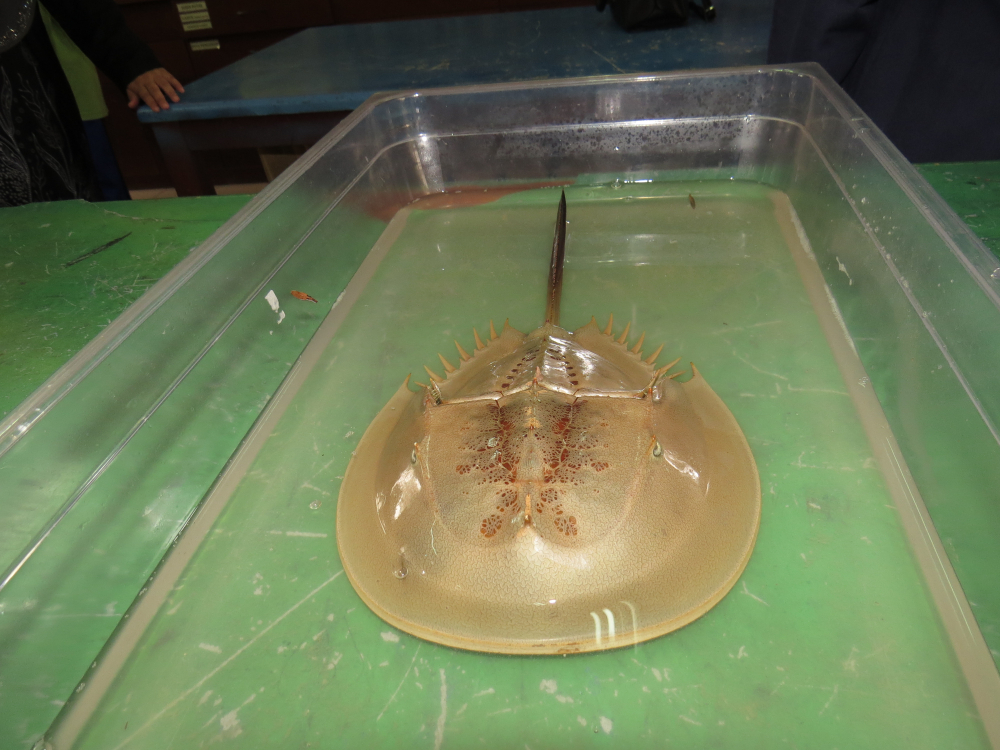

“The first law of intelligent tinkering is to save all the parts,” Leopold instructed. Humans have been tinkering with, altering, extracting from, dumping on, and paving over the Earth forever, and it’s imperative that we reverse the damage we’ve done—to save all the parts, even the unglamorous ones. Did you know that one-fourth of all pharmaceuticals come from or are derived from plant or animal material? For example, the blood from Horseshoe Crabs is used in rabies vaccinations and flue shots. How many plants or animals that we have allowed to become extinct could have contributed to the cure for cancer?

Horseshoe Crab blood is used to make rabies vaccinations and flu shots. The crabs are returned to the wild. Photo credit Adisabariman, Shutterstock

Keys to Puzzles Which We Cannot Solve

Representative Leonor Sullivan of Missouri succinctly stated the reason for the law on the House floor on July 27, 1973, when she introduced the ESA bill. “From the narrowest possible point of view, it is in the best interest of mankind to minimize the losses of genetic variations. The reason is simple: they are potential resources. They are the keys to puzzles which we cannot solve and may provide answers to questions which we have not yet learned to ask,” she stated.

The legislation passed the House 390 to 12, and in the Senate, it passed unanimously. President Richard Nixon signed the bill on December 28, 1973.

The Endangered Species Act is one of the most important environmental laws in the world, protecting plants and animals from extinction even with its limitations. The law currently lists over 1,300 species . . . any one of which could lead to the cure for cancer. Please, let’s save all the parts.

12 Comments

Leave your reply.