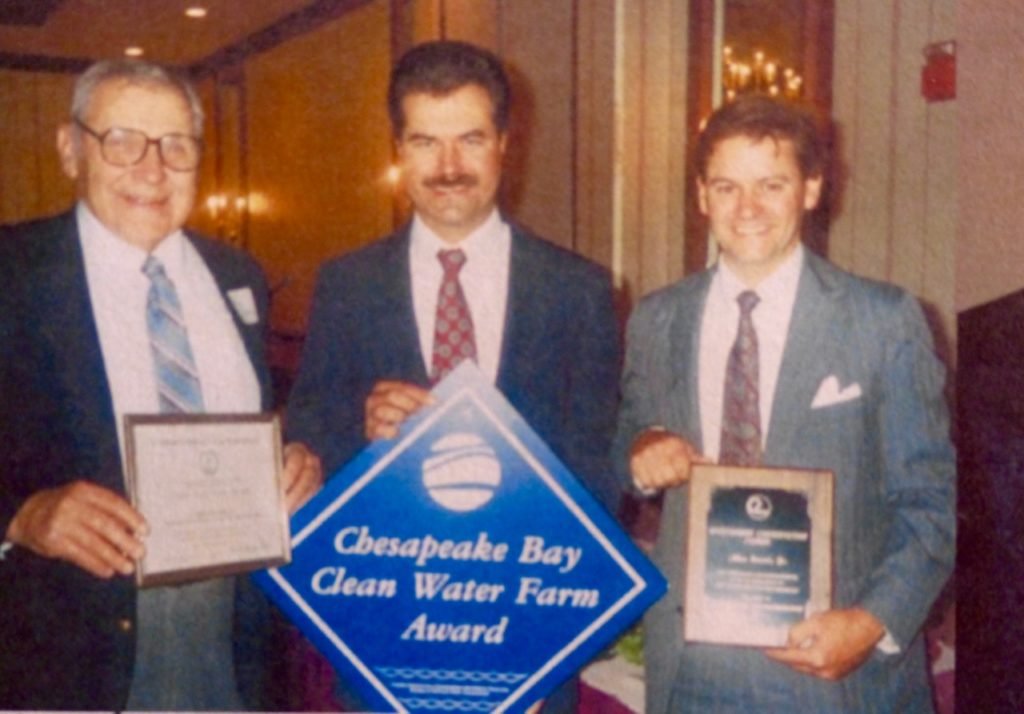

The late Wayne Hypes (left), Allan Bocock, Jr. and Bobby Whitescarver in 1990. Allan received the Chesapeake Bay Clean Water Farm Award for his soil conservation measures.

The story of 2XT and Allan Bocock

Allan Bocock was a grain farmer in Stuarts Draft, Virginia. He planted over 1,000 acres of annual crops each year including corn, soybeans, wheat, and barley. I met Allan in the late 80’s when I moved to the Shenandoah Valley as a District Conservationist for the Soil Conservation Service (SCS). This is the true story of his journey from excessive soil erosion to building healthy soil and how the next farmer – destroyed it all.

1985 Farm Bill – The Food Security Act

I met Allan during the rollout of the 1985 Farm Bill known as the Food Security Act. It was the first time in US history that USDA benefits to farmers were tied to soil conservation. As a result of this law, Soil Conservationists in the Soil Conservation Service were responsible for identifying annual crops grown on “Highly Erodible Land,” informing landowners of this determination and then calculating their current rate of soil erosion. I was in charge of this process in the Headwaters Soil and Water Conservation District.

The “T” value

How much soil can one afford to lose through the acts of erosion and still maintain productivity indefinitely? There is a term for this in soil science called the “Tolerance” value or “T” for short. It’s expressed as tons per acre per year. A ton of soil is about the thickness of a sheet of paper covering one acre; roughly the size of a football field. “T” values range from one to five tons per acre per year. All of the soils in the United States have been mapped, named and analyzed. There is a “T” value for every soil. The data is online at “websoilsuvey”.

The first step in soil conservation on cropland is to make sure soil erosion is at a soil’s “T” value or less. For example, if a soil’s “T” value is two, one can afford to lose no more than two tons of soil per acre per year and still maintain productivity because natural processes will make two tons of soil per acre per year. If one farms in a manner that is below the “T” value, then there will be a net gain in soil. This is the sweet spot in soil conservation – building soil. If one farms in a manner that exceeds the “T” value there will be soil movement downslope. Inevitably this soil will enter a ditch or nearby stream; thereby becoming sediment; the largest pollutant by volume in America’s streams, rivers, estuaries, and lakes.

The great soil erosion compromise – 2XT

Congressional debate prior to the passage of the 1985 Food Security Act was exhaustive. The environmentalists argued that soil erosion on annual cropland should be at the “Tolerance” level for Highly Erodible Land to receive USDA benefits.

The farmers and their lobbyists, on the other hand, didn’t want to have anything to do with more regulation. Farmers loath the thought of some government bureaucrat calculating the amount of soil erosion taking place on in their crop fields.

The result was what I call the “great soil erosion compromise”: The US Farm Bill, still to this day, allows farmers to have twice the soil erosion on their “Highly Erodible Land” than what soil scientists believe is sustainable. We refer to this as “two times ‘T’” or 2XT.

This provision in the law may have been a good example of compromise and democracy, but it was a deplorable example of sustainability.

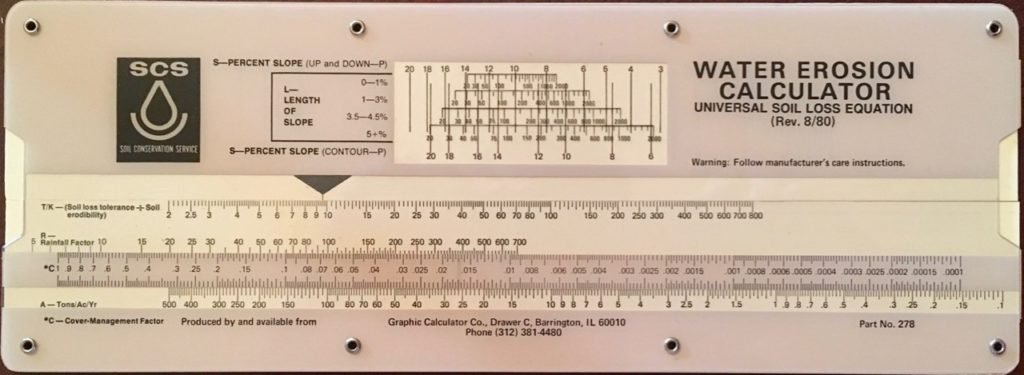

Calculating Soil Loss

In soil conservation, we have a method to calculate a farmer’s average annual soil loss called the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE). It uses six factors that can guide us in developing a cropping system that reduces soil loss to sustainable levels, or to “T”. When I started with the Soil Conservation Service in 1980, we used a slide rule to make the calculations. Today we use the computer and as one can imagine it has become much more complicated.

Universal Soil Loss Equation slide rule calculator used in the 80’s and 90’s to determine average annual soil loss on “Highly Erodible” cropland.

Allan Bocock was farming the most erosion-prone soil in the county

During the rollout of the Farm Bill, I determined that Allan Bocock was indeed planting annual crops on “Highly Erodible Land” and following government procedure at the time, I sent him a certified letter informing him of this determination. Even worse was the fact that he was farming Berks-Weikert, a soil which is shallow, born from shale and highly erodible. This soil has a “T” value of 2 tons per acre per year.

It was a warm and sunny day when I met Allan. I drove along a dirt road to Allan’s farm and turned into the driveway to his shop.

He was a tall, slender man in his late thirty’s with dark hair and a mustache. Hard working, he had black engine grease on his hands. He wiped his hands with a rag and extended one to me.

He showed me around his farm, and I used the USLE slide rule calculator to predict the current average annual soil loss on each of his crop fields.

Allan was farming each crop field in one crop. Wheat here, corn there, soybeans somewhere else, etc. and he was using tillage only when he thought it was necessary. His average annual soil losses were high – exceeding 9XT or over 18 tons of soil loss per acre per year. He was on a downward slope to ruin. As one loses more and more soil, the soil’s productivity decreases and more inputs like fertilizer are needed to produce the same yields as the year before. The top ton of soil is the most productive ton.

We used every BMP in the book

We would have to enlist every Best Management Practice (BMP) I knew of to get him down to “T.” When I explained to Allan about soil health and his calculated soil losses he understood. His desire was to build soil, not have it wash away into nearby streams. He was an excellent candidate for contour strip cropping. Contour farming (across the slope of the land) reduces erosion in half all by itself and increases soil moisture by at least two-fold. By adding strips, or bands of crops alternating with perennial crops it reduces soil erosion in half again. Adding no-till, cover crops and leaving crop residues on the land we could start the process of building soil and soil health. It took us several years to lay out all his land in contour strips.

What resulted was a beautiful landscape of sinuous bands of annual and perennial crops winding their way across the slopes. It was a conservation cropping system; a combination of conservation measures in concert working to produce food, healthy soil and clean water.

This contour strip cropping system on Allan Bocock’s land incorporates many Best Management Practices.

Allan was not only in compliance with the Farm Bill; he was on his way to lowering his input costs and higher profits. As soil productivity increases so does profit. As time went on Allan came to see me several times and told me his yields were going up, and his soils were improving.

A couple of decades later Allan and his wife bought a farm in the Midwest and moved. He rented the Virginia farm to another farmer under the condition that the farmer remains in compliance with the Farm Bill.

The new farmer wanted to use no-till as his only soil conservation measure

That farmer came to see me. He stated he wanted to take the contour strips out and plant all the fields in just one annual crop, and he would use pure no-till in all his operations.

I told him I didn’t think that would work on those very erosive soils but would run the numbers and get back to him.

Well, since the first time I worked with Allan in the late 80’s, the Universal Soil Loss Equation had undergone two revisions. We were in the process of being certified in using the new “Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation II” or RUSLE II for short.

Using the new figures in RUSLE II, “that farmer” had an average annual soil loss of four tons of soil loss per acre per year. In other words, he met the provisions of the 1985 Food Security Act – 2XT.

How could this be? Only one conservation measure, on the most erosive soil in the county in compliance with America’s Farm Bill. (RUSLE II, I found out, gives little to no credit for contour or contour strip cropping when no-till is used.)

I tried my best to convince “that farmer” that what he was about to do was not sustainable. We talked about building soil and productivity. We talked about runoff and soil erosion.

He destroyed all the contour strips and planted just one annual crop – monoculture

My salesmanship skills were insufficient and to my chagrin, all the contours, all the strip cropping, all the perennial crops were ripped out, and all the land was planted to one annual crop. Reduced tillage and no-till are good practices, but we should not rely on these alone to do the important job of building healthy soil and improving water quality.

Aerial infrared photo of the Stuarts Draft, VA area showing many of the contour strips on Allan Bocock’s land. All of them have been destroyed and planted to one annual crop each year.

This farmer and many others like him are able to continue receiving USDA benefits while their calculated annual soil loss is twice what we know is sustainable.

The US Farm Bill is renewed every five years. It’s time to gear up for the next one and time to change the requirements in the law that to receive USDA benefits, soil erosion on annual crop fields must be at “T” or below.

On their farm in the Midwest, Allan, and his wife Linda continue to use Best Management Practices on their land producing food, healthy soil and clean water.

21 Comments

Leave your reply.