Roller coaster capital of the world, Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, is on the Southern shore of Lake Erie.

Sandusky, Ohio and Chesapeake Lessons: It was dark as I drove into the roller coaster capital of the world – Cedar Point amusement park on the shores of Lake Erie. There were life-size mummies, monsters, goblins and witches all over the place. There was one Frankenstein looking monster with Donald Trump hair. “Oh, I get it. They decorated for Halloween”, I thought.

I had to laugh, here I was entering a conference about water quality in the Great Lakes surrounded by roller coasters and haunted creatures.

One of my long time mentors, Verna Harrison, asked me to help her address a group of people in the Great Lakes region on the benefits of having a regional plan for clean water like we have in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. It was the 12th annual conference of the “Great Lakes Coalition”.

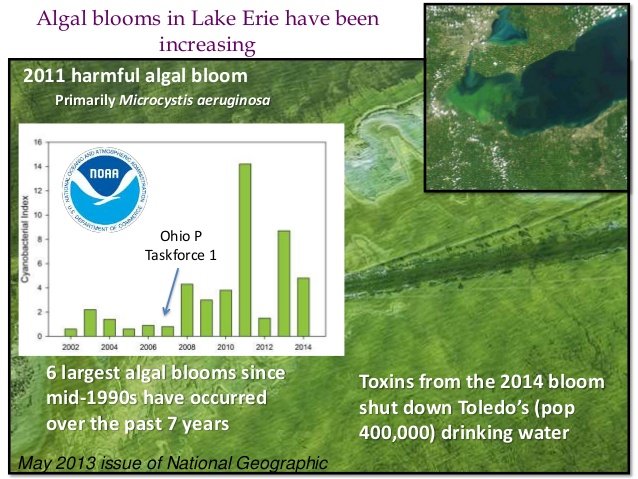

Talk about scary things, Toledo, on the southwestern shore of Lake Erie had the toxic algal bloom in 2014 that shut down the city’s water supply for three days and Flint, Michigan still has lead poisoning from their drinking water infrastructure.

This place, the Great Lakes has certainly had its roller coaster rides and haunts surrounding its water.

The Chesapeake Bay, on the other hand, has had a steady albeit slow, journey to being restored. We have a regional plan to restore the Bay and the streams that feed it. It’s called the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint or the Chesapeake TMDL. According to the EPA, blue crabs are up 92% from last year, water clarity is the best it has been in fifteen years, dead zones are shrinking, all the Bay states except Pennsylvania are on track to meet their 2017 TMDL nutrient and sediment reduction targets.

Sharing Chesapeake Lessons with Great Lakes

I was on a panel, along with Cassandra Pallai, Geospacial Project Manager with the Chesapeake Conservancy, Verna Harrison, Principal, Verna Harrison Associates, LLC and Jeff Corbin, former EPA Senior Advisor to the Administrator for the Chesapeake. We were there to discuss Lessons from the Chesapeake.

From an agricultural standpoint, what could I share with the group assembled in Sandusky? I thought long and hard and came up with four: Our plan, the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working, make nutrient management simpler, verify cover crops via remote sensing, and invest in buffers and buffer maintenance.

Cassandra Pallai, Bobby Whitescarver, Verna Harrison and Jeff Corbin, gave a panel discussion of Lessons Learned in the Chesapeake

The Number One Lesson: The Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working

Our number one lesson for the group was that the Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working. Our Bay is improving. We have reduced nutrients in the Bay in half since 1983; despite the fact our population as increased 30%. That is quite an achievement.

There are many reasons for this. Waste water treatment, Best Management Practices on farmland, oyster restoration, air pollution reduction, reductions in phosphorus from laundry detergent and lawn fertilizers, people doing their part, I could go on and on.

The river that flows through our farm is a tmdl stream and we are in the Chesapeake Bay tmdl as well. These designations have brought program funds into our watershed to help farmers install needed BMPs like cover crops, crop rotation to perennials and riparian buffers. Because of these programs our farm now produces food and clean water; something we are very proud of. These programs created jobs for fence builders, excavation companies, tree planters and other contractors.

Riparian buffers along the Middle River on one of our farms. We enrolled in two programs that helped us install fencing, alternative livestock watering facilities and wildlife habitat.

Those of us in the environmental community think our progress is woefully too slow but the fact is, we are and have been improving the streams and waterways of the Bay steadily and slowly ever since we started the journey in the late 60’s.

For my part of the panel, I presented the following additional lessons that I think we, in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, could improve on.

Make Nutrient Management Simpler.

Chesapeake farmers have greatly improved the use of nutrients on their land and we have developed programs to transport poultry litter from areas with too much of it to areas that need it as fertilizer. But when it comes to phosphorous (P), it’s gotten too complicated and we have not done enough.

We have built billion dollar nutrient management bureaucracies, created phosphorous indexes and management tools that hardly anyone understands, and cut down millions of trees to produce plans that few farmers use. Putting research dollars into figuring out how we can keep applying phosphorus to soils already saturated with it is a waste of time and money that avoids the inevitable: if the soil is saturated with P, don’t apply anymore; Period, with a capital P.

We should invest program dollars in bigger and better P (manure) transport to areas that need it. Phosphorus is a macronutrient in great demand. There are more acres of farmland that need P than ones that have too much.

We also need to begin using crops to remove P from soils saturated with it. Call it agronomic phosphorus extraction from soils or APES for short. (What an acronym? I could not let that one go.) Many say this form of P extraction from the soil, using crops, would take 30 to 100 years. Okay, when do we start? Or do we just keep adding phosphorus at crop uptake levels?

Cover Crops Work but Make Verification Simpler

Farmers in the Chesapeake Bay watershed are planting cover crops like nowhere else. In most areas in Virginia for example, cover crop acres reach 90% of row-crop acres. This is wonderful and reduces both soil erosion and nutrient runoff. Sadly, I was told that the best cover crop county in the Great Lakes region is at best 5%.

Virginia’s cover crop program is a huge success but wastes money in verification and we’ve made to too complicated. To verify that a farmer has planted a cover crop in Virginia’s cost share program a government employee has to drive around in their government vehicles to verify when the crop was planted and if and when the crop was harvested or killed. The programs even dictate what seeds the farmer can use as a cover crop. Most, if not all of this “on the ground” verification could be done via remote sensing and save a lot of time and money.

To streamline the process, just let farmers know that their row-crop acres need to be 100% covered by December 1st. Farmers, I guarantee, will figure out how to get there. We don’t need to dictate what seeds they use, or when they have to plant it.

Riparian Forest Buffers Work but Need Maintenance.

Streams flowing through a forest buffer are two to eight times more capable of processing in-stream pollutants than streams flowing through grassed buffers. That’s because leaves from native trees feed the bugs that eat the pollution. This empirical data comes to us from the Stroud Water Research Center.

Investing in trees along streams makes sense and Chesapeake farmers have planted thousands of acres of riparian forest buffers. To assure success and improve the marketability of these nutrient-filtering carbon sinks, we need to invest more in maintaining these areas. One can’t just plant the trees and walk away expecting a healthy forest in ten years.

A Regional TMDL is working in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed and it can work in the Great Lakes

The Chesapeake Clean Water Blueprint is working. The Bay is getting better and so are the streams that feed it. People from the Great Lakes are in great need of improved nutrient management, cover crops, and forest buffers. They can look to the Chesapeake Bay watershed for a path forward.

26 Comments

Leave your reply.